Dr. Przemysław Strożek

Institute of Art Polish Academy of Sciences / Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk

Dynamics of Futurist Football

Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of Umberto Boccioni’s Dinamismo di un Footballer (1913-2013)

In 1913, when Pro Vercelli won the Italian Championship for the 3rd time in a row, Umberto Boccioni painted Dinamismo di un footballer – most likely the first Futurist and avant-garde painting in which the topic of football appeared.(1) In the course of the year Boccioni was exploring the issues of human body dynamics with such paintings as Dinamismo di un corpo umano and Dinamismo di un ciclista. Dinamismo di un footballer and his two aforementioned paintings formed a kind of triptych on the topic of sport, meant to validate Boccioni’s proclamation from Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto (1910), that ‘the movement and light destroy the materiality of bodies’.(2) The figure of the footballer, caught in the ceaseless simultaneity of the action of kicking a football, would undergo a total dematerialization in the paintings’ dynamical and luminous surroundings. The silhouette of the moving footballer anticipated the theory of plastic dynamism, according to which ‘dynamic form is a species of fourth dimension in painting and sculpture’.(3) Boccioni expressed the need to introduce a dynamic element in painting so that the subject would seem to be in constant motion. The truth of the modern, quickly changing world was to be expressed by omnipresent dynamism. This is why Boccioni introduced elements connected to sports in his paintings – they allowed him to try and depict dynamic continuity as a single form.

Dinamismo di un footballer did not convey the atmosphere of the stadium – the field, the goalposts, the spectator stands, or the competing footballers. Were it not for the title, it would have been difficult to guess that football was its subject at all. Boccioni depicted a footballer, shaping his body so as to maximise his physical force, expressing the health and virility of the new century appealing to the masses. Painted in such way that he rises above the ground, the footballer seems to be making movements similar to those of airplane propellers. Boccioni thus explored the mechanical aspects of movement – muscles built to resemble those of a machine. It appears that Dinamismo di un footballer not only referenced the theory of plastic dynamism, but was also an allegory of the new man, of a superhero. It is no accident that Boccioni’s painting was one of Marinetti’s favourites – it hung in the central point of his Rome apartment. All in all, Dinamismo di un footballer constituted one of the greatest achievements of Futurist painting, where all that was dynamic, mechanical and modern merged with the vision of the Futurist superhuman.

When it comes to painterly ‘dynamisation’ of the human form, the motive of ‘a footballer in movement’ resurfaced in the years to follow in the works of successive generations of Italian Futurists. At the beginning of the 1920s, impressions of football matches appeared in Iras Baldessari’s Giocatori di pallone (1920); Emilio Notte’s Partita di pallone (1920); Enrico Castello’s Calciatori (1920) and Il portiere (1922). These works showed footballers caught in the moment of field rivalry. Notte and Castello explored above all the dynamics of a football game – the competitivity, the struggle of muscular bodies. Baldessari in turn presented the footballers’ silhouettes as a composition of geometric forms, placing them not so much within the Futurist aesthetic as somewhere between Cubism and Constructivism.

At the beginning of the 1920s, Fortunato Depero created a series of sketches entitled Giocatori di pallone (1920-21), which examined the phases of movement of a footballer approaching a goalpost. The analysis of the stages of movement resembled an intervention not unlike Ettiene-Jules Marey’s chronophotography. The latter had used photography to track physiological functions and mapped out the transformation of corporeal energies while his subjects performed different movements. The silhouette of Depero’s footballer, with its shape of a dummy, resembled the characteristic toys (‘giocatoli Futuristi’) designed by the painter for the Casa d’Arte Futurista (founded in Rovereto in 1919), and the footballer-dummy’s kinetic phases of movement were evocative of his puppet theatre sketches.

After 1926, when the fascist government seized control of calico and issued Carta di Vareggio, which reorganized, rationalized and nationalized the game, the subject matter of football would return in the art of the Futurists with additional force. One of the main representatives of Secondo Futurismo, Gerardo Dottori, created at the time a series of sketches called Appunti allo stadio which depicted a number of particular football situations. It had little to do with the Futurist aesthetic, but it indicated the painter’s particular interest in the subject. In 1928, he created one of his most known paintings Partita di calcio, in which the football players were surrounded by a landscape simultaneously rendered dynamic by circular forms, diverse perspectives, dimensions and scales. The players had been inscribed in rays of refracted light, which resembled Boccioni’s solutions from Dinamismo di un footballer. Yet in Dottori’s work, the silhouettes of the footballers’ moving bodies did not dematerialise so radically. The competing players were soaring towards the sky as if being drawn in by the sunlight, evoking Dottori’s use of refracted rays in his religious and landscape paintings of central Italy. This ascension of footballers takes place among the forests of Umbria, and is seen from an aerial point of view. In the entire scene one distinguishes players sporting blue shirts and white shorts. The national colours of Gli Azzurri suggest that the game depicted in Partita di calcio is taking place at an international level. In the 1928 Summer Olympics tournament in Amsterdam, which is described as the precursor to the first FIFA World Cup held in 1930 in Uruguay, Italy won the bronze medal. Partita di calcio might thus have been a painterly variation on one of the games, set in the local landscape of Umbria; it might also have been an idealisation of the first international successes of Italy’s national team.

Between 1928 and 1930, many Futurist painters turned to motifs connected to football. Among them were Pippo Rizzo, Vittorio Corona, Tato, Thayaht, Ivanhoe Gambini and Giulio D’Anna. A sketch by D’Anna entitled Calciatore (1930) bears a striking resemblance to the silhouette of the new 20th century hero: Boccioni’s sculpture Forme Uniche dalla Continuita’ nello spazio (1913), which sought to exemplify Marinetti’s dream of a man/machine hybrid.(4) D’Anna’s footballer resembled a soldier marching in the war, but here his intention was to catch the ball, and his duty – to shoot on goal.

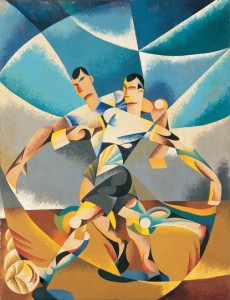

Three years later, Giulio D’Anna revisited football as a subject matter, once again referring to Boccioni’s oeuvre. In a 1933 painting called Football, he created the illusion of a running footballer, caught in the simultaneous action of taking aim and kicking the ball. D’Anna displayed the stages of movement, and as a consequence the footballer becomes two people – two heads, four arms, four legs. Such way of expressing the dynamics of a sportsman perfectly matched the fragment of a Futurist painting manifesto, where Boccioni, still in 1910, wrote: ‘On account of the persistency of an image upon the retina, moving objects constantly multiply themselves; their form changes like rapid vibrations, in their mad career. Thus a running horse has not four legs, but twenty, and their movements are triangular’.(5) This painting, like many others, is a testament tothe vitality of Boccioni’s ideas among the younger generations of Futurist painters. Dinamismo di un footballer continued in the 1930s to function as a model for the Futurist imagining of the dynamics of a footballer’s silhouette.

[Published 3/31/13 ItalianFuturism.org, © Przemysław Strożek. Above text is a fragment of an essay Football, in Futurismo. A Microhistory, forthcoming 2013]

NOTES

1) Up until that time, French modern painters Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay and André Lhote painted fragments of games, often entitling them ‘football’, but in reality painted rugby games. This indicates that in Europe the names of both games were not fully precise yet. Rugby was historically a form of football (the main association is still called Rugby Football Union, RFU) and it was only in the late 1800s that it split from ‘association football’ which is the present form of football.

2) Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto 1910, in Futurist Manifestos, ed. and introduction by Umbro Apollonio (New York: The Viking Press, 1973), p. 30.

3) U. Boccioni, Plastic Dynamism 1913, in Futurist Manifestos, p. 93.

4) Ch. Poggi, Inventing Futurism. The Art and Politics of Artificial Optimism, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), p. 170.

5) U. Boccioni [et. al.], ‘Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto 1910’, in Futurist Manifestos, p. 28.

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT FUTURISM AND FOOTBALL (SOCCER):

Appunti allo stadio: 90 opere sul tema del calcio nell’Arte italiana del XX secolo